Voice Institute

Dark Voices

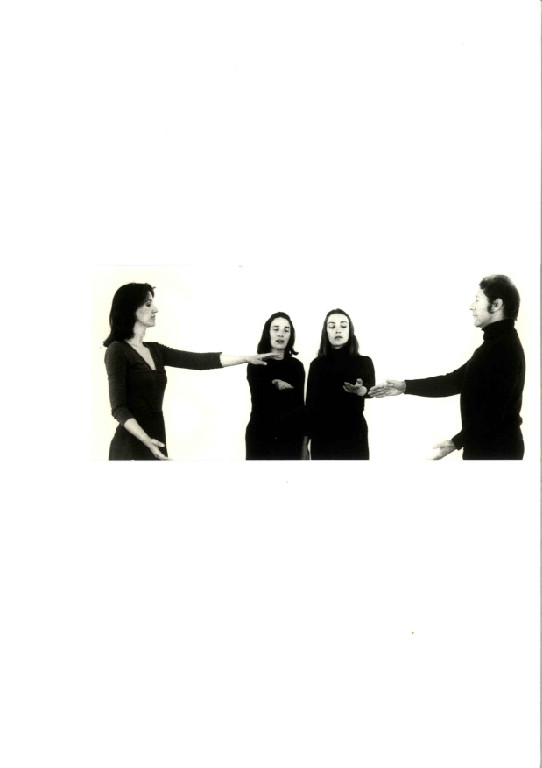

Vivienne Young, Dorothy Hart, Lucienne Deschamps, Roy Hart in L'Economiste, 1975. Photo Ivan Midderigh

from Dark Voices

Chapter Six

Paul Silber Remembers

18 May 1975

It was about 10 o’clock on a lovely spring morning in the month of May. It was the 18th May, and the year was 1975. Dorothy Hart had just had her 49th birthday 10 days before, on the 8th, and I had my 37th birthday just five days before, on the 13th. What a beautiful sunny day it was. Warm, warm enough for me to travel in the car wearing only my shorts. A very gentle wind was blowing in from the Mediterranean coast, not far from where we were, just inland from Nice. We packed up the bags and put them in the boot of the car, which with four people’s luggage in it, was then completely full. It was a Sunday morning out of the tourist season, before even the real beginning of what now passes for tourism, on that vastly overestimated stretch of coast, even existed. There was nothing else moving on those roads at all on that beautiful sunny Sunday. So sunny and so warm was it that we decided that we would rather travel along with the sliding sunroof of the car wide open. We had, as usual, spent rather longer than was wise over our breakfast. This was because, as usual, we had to have an analysis of our dreams before setting off.

I had had an amazing dream that night which Roy and Dorothy had entitled “The Phoenix Dream.” How extraordinary, in the light of what was about to happen, that they interpreted the dream with that particular word. This was also the famous occasion when Roy, having heard the contents of all the letters coming from Malérargues, commented that “there are no leaders in Malérargues,” and he said this with great sadness in his voice. As it turned out this was subsequently proven to be entirely true.

When we realized what time it was, there was something of an emergency on our hands. We still had to get all the way around the Mediterranean coast to Barcelona by nightfall. It was a Sunday, a very quiet Sunday in a very sleepy southern France, we had very little petrol left in the tank and we looked all around the town of Nice for an open petrol station, there were none. We drove on to the Auto-Route hoping there could be one open there, and after a while we found one. I had been driving the BMW 2.2 up until then, by now it was about 11:30 a.m. We filled up and we were about to re-enter the car to continue on our way, when Vivienne asked Roy, “Can I drive the car for a while now Roy?”

“Well, Paul, what have you to say about that?”

There was an inordinately long pause. Normally Roy would have commented on such a long pause as being bad theatre, but nothing, strange, very strange. In the absence of anything else being said, Roy then said, “Well then that’s settled. Vivienne you will drive.”

I felt strangely sad and put down. Vivienne got into the driving seat. There were very few minutes left.

We drove out of the petrol station and on to the Auto-Route, we started to pick up speed. The atmosphere in the car was calm, very calm, almost serene. Dorothy especially was happy and quiet, she was sitting next to me in the back, she was writing a letter to her family in Scotland. Roy was reading his book in the front with Vivienne. She was to his right as it was an English car. We began to take a very long slow turn to the left. Then we were moving at 130 km/h.

Vivienne turned to look at Roy. Then a very strange thing happened, Roy turned to look back at Vivienne. He would never have done such a thing normally. He would have immediately said, “Concentrate Vivienne, keep your eyes on the road.” Nothing, strange, very strange.

How long did they look at each other? Three, four, five seconds? I don’t know how long it lasted, it seemed to me a very long time. They were in love with each other, perhaps this is enough to explain everything that happened, I think not all of it however.

When Vivienne turned her eyes back to look on to the road she found that the car had been moving on in a straight line, the road, however, had been slowly turning to the left, the car was already on the hard shoulder, very near the edge of the Auto-Route. There was a row of little wooden pegs with red tops sticking up out of the soil in a line just off the Auto-Route’s edge. Beyond this there was a field that was on the same level as the Auto-Route. Vivienne was not an experienced driver, she had only passed her driving test a few months before. Just the slightest easing of the wheels to the left would have been sufficient to correct the problem but no, she was surprised by the nearness of the edge. She gave the wheel a hard yank to the left and we started on our last journey. The car turned too hard to the left, Vivienne tried to correct it, turning to the right, too hard again. I don’t know how many times we skidded first to the right and then to the left and then back again. It seemed to me that it was quite a few times. Roy had put his book down on his lap, he was looking straight in front of him, he had on his lips a strange little smile. He never, wisely, tried to give any help to Vivienne in her fight with the control of the car. I was sitting very upright, right between the two front seats holding on to the back of them, one with each of my hands. I was very tense, stiff even, with fear, these are facts which together came to save my life.

After the third or fourth attempted correction of the wild careering of the car had passed without any effect, the final stage that was to end everything, was already close at hand. The rear right-hand wheel collapsed, it folded in underneath itself, then there was nothing left that any of us could do anymore, it was all finished. The car started to spin around to its left, the speed must still have been over 100 km/h. The remaining three supporting wheels under the car were insufficient for it to remain upright. It turned over on its roof, onto its beautiful sunshine roof and there it was, completely friction-free. The car was able to spin around at great speed about its own axis, like a spinning top, throwing all its contents all over the road all around it.

I had been the first to be thrown out of the car. Because of my central position in the body of the car, I had been thrown out cleanly through the rear window, breaking it first with the crown of my head. Fortunately I had passed out just before all this was to happen whilst sitting inside the car. The BMW 2.2 of that epoch was the first of its kind that had a big enough back window to allow a human body to pass through it. Even so, to do so at that speed, without hitting the spinning metal cages (these were razor sharp) that were left there after the rubber seal had been broken out, was already a miracle. Poor Dorothy, she was not so lucky, she also was thrown out of the back window of the car after me, but because she was in the corner of the car, she was thrown out while turning sideways through the air, hitting the metal edges of the window as she went through it.

Roy and Vivienne? They had not been wearing their seat belt, had they done so they might well be alive and well today. The centrifugal force of the car spinning on its roof had thrown them forward through the front window, unfortunately their legs being under the dashboard of the car, these were caught, their bodies were folded over the dashboard, their heads having already broken through the front windscreen, they were unable to be either thrown out clear of the car’s wreckage out on to the road, nor to remain intact within the body of the car. They died from their stomach wounds.

The last and the greatest of the miracles that saved me that day was that at the moment when I was thrown out of the car while it was spinning around upside-down, it happened that the back end of the car was facing in the direction along which the car had originally been moving in the first place. The speed of my ejection through the window was therefore slightly reduced in relation to the original speed of the car. I landed on the back of my poor head and on the top of my naked shoulders. It says something for the suppleness of my back that I was able to take up the speed of my movement by rolling over the glass strewn around, over and over, head over heels along the hard shoulder of the Auto-Route until I also came, at last, to a stop.

At this time I was completely unconscious. Somehow, even in the depths of my unconscious, I must have known something of what was going on. Something deep within me must have wanted, with a great need, to say my final goodbye to Roy and Dorothy for the last time. I partially came to for a few instants. In that state of consciousness, what I saw and felt before me was the following: Firstly that I was buried horizontally in the ground up to my neck (that must have been an indication of that amount of pain I was suffering). The second thing I saw was Roy. It seemed to me that he was lying on his side in a fetal position in the sand of a great desert. I could hear the gentle sound of the wind blowing. Behind him was a great boulder. It was calm, very calm, serenely calm. That was the last time I ever saw my dear sweet friend Dorothy Hart and my loving father Roy Hart.

Twenty four years later, I can unambiguously state that in all the years that have passed since their deaths no one and no thing has ever filled the vacuum in the world of theatre that their deaths left behind them.

I woke up that Sunday afternoon in an overheated hospital room pouring with sweat, the sunshine still pouring in through the window, having the skin under my left eye and under my nose being sewn up by a young doctor, who didn’t know what to do with an even younger patient, who was supposed to be still asleep and certainly not supposed to be suffering any of the pain that I was suffering from. I was in the hospital for two days. It was in there that I learned for the first time consciously that Roy and Dorothy were indeed dead. It was both for me personally and for the world in general a very sad end of a very great epoch that was never to be replaced. On that day in May, the whole world of Western European culture took, along with Roy and Dorothy, a slow turn to the left, a turn out of the consciousness that Roy was proposing for THEATRE, and into the backwards spin of the safety of drawing room performance energy. One has only to look at the standard of acting in today’s theatres to realize the truth of this.

Davide Crawford came and removed me from the care of the hospital two days later. Both the doctors and the nurses were very much against my being released. The Roy Hart Theatre could not afford for me to remain in the hospital any longer, thus greatly risking my future health. (Why either the car insurance and/or my English social security couldn’t have covered the cost of all this, I will never know.) I remember one of the nurses on hearing the news told me, “It is not possible for you to leave the hospital now” and immediately she spun me around and picked out, causing me great pain, a piece of shattered glass from my back. I remember that I had to sign a paper that released the hospital from any medical liability in view of my untimely release from their care. It was true that for many months after that, little pieces of glass would emerge unexpectedly from my body at unexpected times and in unexpected places.

My journey from Nice back to Malérargues was the most macabre I have ever undertaken in my life. It took place in a little hired van, in it with me were the three plain wooden coffins containing the bodies of my three dead friends.

Within two weeks of my return to Malérargues, we were again rehearsing “L’Economiste.” What possessed us to do this I cannot imagine. For us to have attempted to insert our own little selves into the places of those, our lost giants of theatre, was an act of the greatest possible folly. However this is what we insisted on doing. I remember that during the warm-ups in those early mornings, I would notice from day to day the strangest progression in the movement of a pain passing through my whole body. It would take a rhythm of three to four days in each place. It would start in my right elbow and pass through to my right shoulder, then it would go over to my left shoulder, then it would slide down to my left elbow. And then it would pass back to my left shoulder, then across to the right shoulder again, and so on and so on. In the end I went to a doctor and was prescribed a serum to be injected into my arm against tennis elbow, would you believe it? Interestingly, I had a dream at that moment in time in which I took the serum back to the doctor who had given it to me in the first place. In any event the treatment had absolutely no effect on me whatsoever. I can no longer remember any more when I first experienced that agony of my shoulder dislocating itself. But I have no doubt whatsoever that this was caused directly as a result of the car accident. Over the years since then, I have no idea how many times this dislocation recurred, but it was many times. Finally it came to such a point that it was so used to coming out of joint that even an act as simple as drawing a curtain back would allow it to come out, always with the same terrible agonizing pain. So, at last it was decided that the problem could be cured by an operation being performed on it. This was duly done in the Clinique of Ganges and after some re-education on it for a little time afterwards it became all right again. I have subsequently never had any trouble with it ever again.

As the time moves further and further away from the date of the accident, it becomes less and less sure whether the problems in my other joints were directly related to the accident or not. It seems quite possible, however, that these more recent weaknesses were also induced by the shock of the accident.

All that I have said above still cannot satisfactorily account for how I managed to survive the terrible forces at work in that accident. Clearly there must have also been forces at work that sunny day that can only be described as being those of a supernatural order. For myself, the miracle of my survival from that terrible accident in the face of all my friends’ deaths, can be more than explained by the fullness of the life that I have been able to live since that time. I have found solace in the fact that many people have been personally helped and creatively guided by the voice work that was inspired by Roy Hart and was transmitted by myself and Clara, my wife, in the many workshops and performances that we have given in the twenty four years that have passed since that terrible day in May 1975.

The End

Paul Silber

1999, Malérargues, Thoiras, France

Only Silence

(Noah Pikes follows with this reflection after Paul Silber’s account above)

I was en route from Vienna to Barcelona that day with the rest of the cast of L’Economiste. A stop-over at a hotel in Nice had been prearranged, and it was there that we heard of the fatal accident, relayed to us from Malérargues. Apart from cries by myself and Vincente, there was almost no vocal reaction on hearing the news but instead only silence. Later that day I sat for hours with Barry on the pebbled beach beneath the Promenade des Anglais gazing out to sea, with the question, “Do I leave now?” slowly crystalising on the horizon. Many years later I discovered that this question arose in the minds of others, too.

To have answered “yes” would have been to agree with all those who had projected an image of fascist or guru onto Roy and of “docile followers” onto us. For me it seemed a denial of the years of struggle towards becoming an individual. For all of us, it would have been to abandon the “Idea” we had come to serve and love. In recent months Roy had hinted at some kind of a separation to come once the move from London was complete. He would not live in Malérargues but up on the hillside in a chalet already known as “Roy’s Chalet,” and his sadness at the lack of leaders among those now there was part of this picture.

But why so brutal a parting? What would become of us? Now was the moment of greatest peril, and Roy had been preparing us to face it. In the previous years he had more than once referred to his mortality. In 1971 he wrote to us all from abroad:

“If you hang on to each other it means that you are afraid to die, which you must…sometime, perhaps soon…this is not a morbid thought. It is a fact, live serenely in this knowledge, make every smile count, every tear a joyful encouragement, every gesture a healing one, in short be compassionate. Don’t hang on—let go: and sing.”

“The death I’m talking about must and does lead to life; because it implies control and discipline. The control and discipline I’m talking about means that death has no dominion, because I know that it is there, by my side, making me feel more, want more, live more.”

© Copyright 1997 Noah Pikes